Kurt Snoekx© BRUZZ. 21/05/2020 16.19u

https://www.bruzz.be/en/culture/art-books/tan-tan-wuhan-inside-look-misplaced-city-2020-05-21

Until the autumn of last year, Wuhan-born artist Tan Tan divided her time between Ghent, China, and Brussels. On 23 January, she was visiting her parents for Chinese New Year, when her place of birth went into total lockdown due to the Covid-19 outbreak. For over two months, she kept a diary to document her confinement and confrontation with an unknown disaster.

WHO IS TAN TAN?

“Could this be the end of the world? That was the kind of panic that came over me, as it became clear that the situation was way more serious than when SARS hit Beijing in 2003. How could I know I would survive?” Tan Tan tells us from a more peaceful time and place in China. On 8 April, the complete lockdown that had been imposed in Wuhan since 23 January was eased, and after having spent all those weeks in isolation with her parents, the artist went to find a quieter place to stay outside the city.

Tan Tan

During those two-and-a-half months in isolation, in “the city where it all started”, Tan Tan would tell her story before midnight every day in her “Diary under Wuhan Lockdown”, posted on the WeChat Friends Circle, a popular social networking platform in China. It was a way to share her personal experiences in confinement and offered an insight into a wide array of feelings, ranging from panic to redemption, from anxiety to anger, and from sadness to depression. Her story struck a sensitive chord and was transformed into a beautiful, spirited essay on the Misplaced Women? blog (edited and first published by Tanja Ostojic on 5 April).

A generous gesture, a warm embrace, and a possible support for those “who are still struggling with the quarantine.” Because it can be of some solace to see the effects of doubt and uncertainty in someone's else headspace, to see how panic and unrest can sometimes overwhelm the most stable person, how valuable the little things are, and how more “together” we – unwillingly folded back on ourselves – really are.

“It was actually a close friend of mine who suggested I keep a diary. At the time, I didn't know how long we would have to wait for our lives to be 'unlocked'. So I decided to begin a diary to at least have a souvenir of this unusual situation,” Tan Tan explains. It is some time ago since she erupted onto the arts scene with films and videos, performances, theatre, music and sound pieces, installations, and cyber art. Rebellious and experimental experiences that are staged and screened both in Brussels, the city she fell in love with in 2012 and where she has lived part-time since 2015, and abroad – at the Berlinale, Elles Tournent, the film festivals of Rotterdam and Göteborg, Le Clignoteur, and the Venice Biennial, where she staged a non-authorised intervention together with the Brussels photographer Sophie Saporosi and the Brussels musician Eric Bribosia.

“Of course I kept in touch with my friends in Brussels,” Tan Tan stresses. “In January and February, they often asked me about my situation. As of March, it was my turn to care about them. I feel our experiences and emotions were quite similar, despite the fact that we were living on different continents.”

Whatever the differences, both your experiences and your diary struck a universal chord. Those diary entries were combined with pictures of the view from your window. Across the lake you can see Central South Hospital of Wuhan University. What were you looking for in those pictures?

Tan Tan: I wasn't really looking to “find” anything at first. I just wanted to express the feeling of being “frozen”, by posting the same image frame and landscape every day. But gradually I started to notice the light shift, the trees turn green, the flowers blossom, and the air clear up. It was then that the meaning of my photos surfaced. What moved me most was the vitality of nature without human interference, the reciprocity between humans and nature.

A room with a view: photos from Tan Tan’s Diary under Wuhan Lockdown

The window through which you took those photos is at your parents' house, isn't it?

Tan Tan: Yes, it's a flat in a nine-floor apartment building. Luckily, there are two balconies, one of which faces a lake. But we weren't able to talk to any neighbours on the balconies, due to the structure of the building.

You spent a total of two-and-a-half months in confinement there. How did you end up in Wuhan, and at your parents' place, at that particular time? Was news about the virus not already circulating?

Tan Tan: I left Belgium for Wuhan in the autumn of 2019, to take a break from my PhD. I have my own home in the city, but I often go to stay with my parents for a few days, because of the distance and the traffic between my home and theirs. It’s also a habit as I am an only child – like many other Chinese people who were born after the introduction of the 1978 one-child policy. My parents and I were going to celebrate Chinese New Year together on 25 January.

News about the virus had circulated since the beginning of January, but for a while we were being told that the disease could not be transmitted between people, so no one really cared. Around 18 January, the situation grew severe, and so I wanted to be with my parents to try and protect them. But I never imagined that I would be locked in with them and would not be allowed to go back to my own home for such a long time.

I think we have all been isolated long before the coronavirus outbreak. People have forgotten about their fundamental spiritual bond with the universe and others

Tan Tan, artist between Wuhan and Brussels

In your text “Misplaced Self in the Misplaced City”, you write very movingly about the living with your parents, and about how you take on the disguise of the “good girl” in their presence. And then there is the last sentence, that cuts like a knife: “I have lost my integrity, my real world and space, and have been living with a 'misplaced self.'” How did you cope?

Tan Tan: I think Xavier Rudd expresses it best in “Creating a Dream”: “Imagine everywhere was free to roam. Imagine if the trees could tell us where to go. Imagine that the sun could fill each lonely heart. Please patience please patience please, I'm creating a dream.” My parents don't really understand me, but I still love them. I think we shall continue to love with patience.

PUNK SPIRIT AND DESTINY

It is not only Tan Tan's self that felt “misplaced”. She lived through the lockdown in what she calls a “misplaced city”. Wuhan has come under severe criticism since the outbreak of Covid-19. The coronavirus lay over the city and its inhabitants like a stain, influenced by a deficient domestic approach and venomous foreign tongues. “It was truly painful to see my place of birth being accused of creating a virus,” says Tan Tan. “This ridiculous immorality still exists, and is on the rise. I myself as a Wuhan citizen have experienced discrimination in China, and I have heard of Chinese and Asian people abroad who have had to deal with racism due to Covid-19. These kinds of accusations go against universal humanity.”

As you write: “We are all vulnerable, useless, uninformed/overinformed, and under a quarantine with an unpredictable end. We are all isolated and ‘misplaced’ in this incredible situation.” Why do you think people – even in times of crisis – find it so hard to unite?

Tan Tan: That’s the ultimate question, and I don’t have a clear answer to that. But my guess is that we have all been isolated long before the coronavirus outbreak. As the world has been driven more and more by material and economic forces, people have forgotten about their fundamental spiritual bond with the universe and others.

Wuhan is your city of birth, the place where you grew up. What should we know about it?

Tan Tan: There's so much to tell! Wuhan is home to about 14 million people and covers a massive area of 8494.41 km² – that's roughly 80 times the size of Paris. Wuhan is also the city with the most urban lakes in China. But it is also called the “City of the River”, because the Yangtze runs right through the city centre.

Wuhan on 23 February

From a personal point of view, I think three things have made me into who I am. First of all: the water. I have lived near a lake practically all my life, and I love watching the sun rise and set over the water. If there is one thing that I missed most in Brussels, it is the water. Strangely enough, I never learned how to swim. (Laughs)

The second thing is linked to the fact that Wuhan is an “inner-migrant” city in China. It has the biggest population of university students in the country, and its central position allows people to travel easily. So since my childhood, I have met people from different provinces, speaking diverse dialects. Maybe that is why I feel at ease in Brussels, this multicultural city that I have a destiny to mingle with. In Chinese, we call that yuan fen, something like karma in Buddhism.

And finally, Wuhan is also home to a lot of subcultures. China has long been closed off from the outside world. Even today, Chinese culture isn't as pluralistic as Western culture. But Wuhan is an extraordinary exception: it has punk music, underground electro parties, tattoo shops, cosplay, cutting-edge fine arts, and an LGBTQ community. These things are still frequently criticized in China as they sometimes advocate values that aren't part of mainstream society. I guess I was unconsciously injected with some of that punk spirit while growing up; it charges me with an inner power to create “rebellious” art.

Tan Tan at the beginning of May, on her first trip outside of Wuhan

How did the pandemic affect you as an artist? I can feel your struggle with its “usefulness” in your text.

Tan Tan: I have known that art isn't so “useful” for a long time. Especially in China, a lot of people doubt if being an artist is actually a real career and many parents teach their children to become “useful people.” Maybe that's why my PhD is about socially engaged art, to prove that art can intervene in social reality. Then again, art is still only art. It's not a cure that saves lives.

My idea about art hasn't really changed during the lockdown. I think at times, I just felt a bit cynical about the place of art in the world. If anything changed, it was my consciousness about what I want to do as a human, whether it be through art or not. That's why right now, I give more attention to things like animal advocacy, environmental protection, and spiritual healing.

Were you still able to create during the confinement?

Tan Tan: Well, most of my time was dedicated to writing my dissertation, but I continued to create, yes: I wrote plans for a new theatre performance, recorded vocals for a few new songs, did the mixing of my music and sound pieces, and I took part in two online exhibitions. There have been a lot of online art initiatives since February. Next to that, I also wrote articles and answered interviews about the epidemic on several online media. I do many different things. (Laughs) I think keeping myself busy is a good way to relieve myself of negative emotions.

Another thing you did was to become a volunteer with the Lumo Road Rescue Group, a collective made up of rock fans, artists, hippies, musicians, university students, and other night owls. What did you do?

Tan Tan: That happened very unexpectedly. At first, I just spontaneously shared the posts from the Lumo Road Rescue Group on the WeChat Friends Circle. In return I received an enormous number of messages from people seeking help or offering donations. I realized that I could use these contacts to solve practical problems, and I began to build “networks” for a whole week. For example, I connected a donor, who was introduced by a friend, with a voluntary driver of the group, and would then ask the driver to send the supplies to a doctor, who was in turn introduced by another acquaintance. My wrists still hurt from all that tapping on my cell phone.

I have a destiny to mingle with Brussels. In Chinese, we call that “yuan fen”, something like karma in Buddhism

Tan Tan, artist between Wuhan and Brussels

But that didn't alleviate your anxiety?

Tan Tan: We did help a lot of hospitals and raised a lot of money. But the lack of supplies was too great to be met by this spontaneous group of individuals. Also, the government started to control the sources of the medical supplies and monitoring the donations. In January, we felt that the bureaucratic administration often caused a delay in the distribution of supplies. What we did was skip official routes and put those things directly into the hands of those in need. By the end of the month, these Robin Hood-like actions became much harder. That's where my anxiety came from. Luckily, from February onwards, better governmental measures and more donations countered the lack of supplies day by day.

ELVISH WHISTLES

That is also Tan Tan's story: the story of one small person in a slow, lumbering machine. A story of criticism and pride, of cohesion and isolation. Of a search for a new balance, via the route of creative resistance, sometimes fuelled by anger. “In the beginning, I was often angry about the Covid-19 measures in China,” she writes, at a time when reports were reaching the West about threats to doctors who had raised their voices.

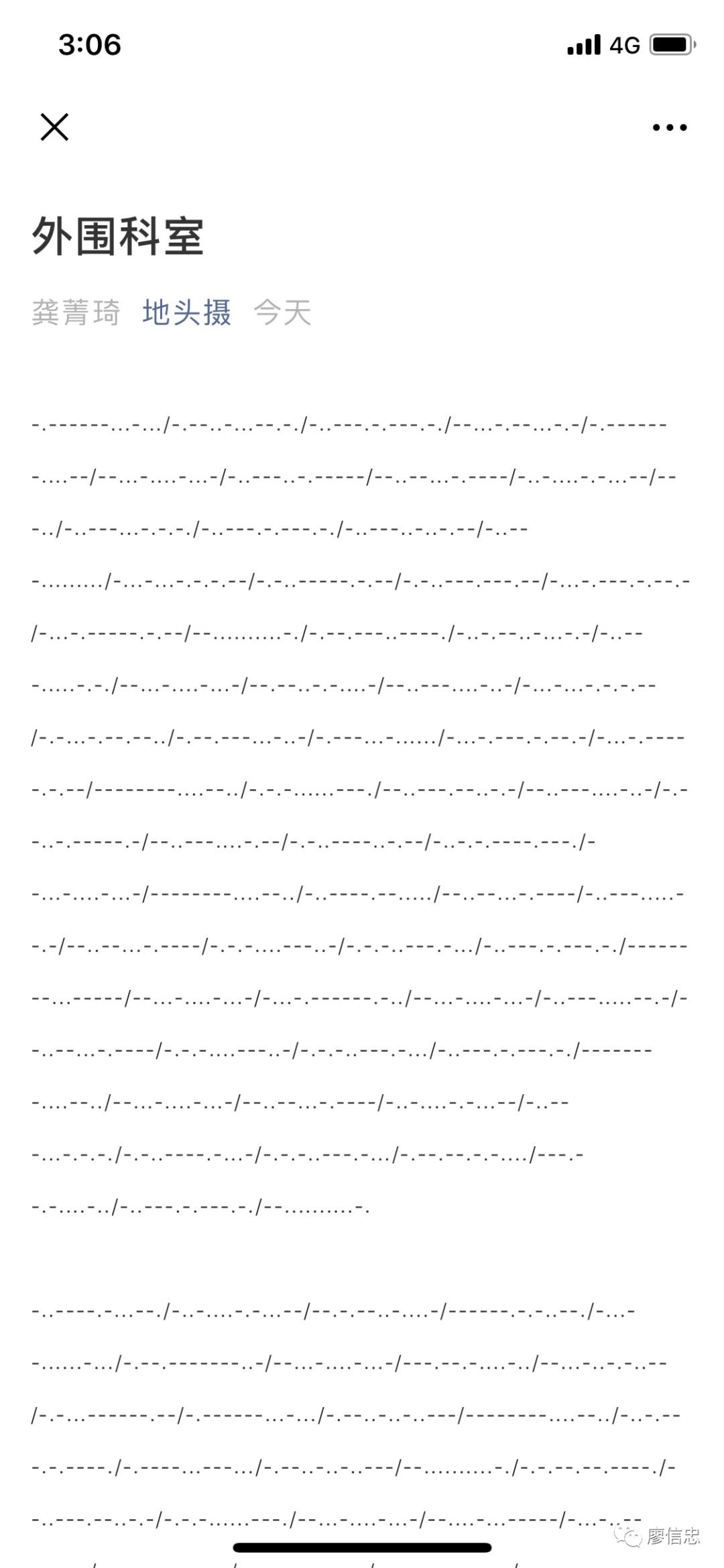

“It isn't easy to express this kind of criticism,” she says. “I myself haven't seen the real 'truth'. But you can find images online of messages sent by Chinese people, in all kinds of languages, images, codes, and secret signs – even Elvish, Klingon, and Morse – to spread the news about Ai Fen. She was one of the first doctors to come into contact with the virus and she already sounded the alarm in December. She is now regarded as 'The Whistle-Giver' by the media, the person who provided whistle-blower Li Wenliang with the whistle. All of these laborious efforts by the 'netizens' were meant to avoid censorship from the authorities and keep the news online. Many people see it as the largest piece of performance art done by a random collective in Chinese history.”

The art of whistleblowing: “the largest piece of performance art in Chinese history”

At the same time, Europeans often get the impression that the Chinese had an easier time dealing with the lockdown.

Tan Tan: It was in no way easier! It might look that way, but that would be due to two reasons. The first is linked to the different social systems in China and Europe, as perceived in the media, giving China the edge in a prompt execution of orders. Secondly, what I personally think is more crucial, is the slight difference in what people consider to be important.

For example, I think the Chinese are, generally speaking, more obedient to government measures, while Europeans value freedom and democracy more. In China, for example, there were nearly no administrative penalties for people wandering in the streets, like you had in Italy, France or even Belgium. My mother only went out after 84 days! She just thought it was safer, and saw her compliance as a way to help the government get a grip on the situation. There are a lot of people like her in China.

In my opinion, this obedience is not only due to the current political system, but is deeply rooted in a cultural history of thousands of years. But there are others who are less obedient. (Smiles) We do our best to make the right things happen, even if it's not easy.

Here, we obeyed our instincts, which...well...led to a rush on toilet paper. Have you experienced the same kind of rush on goods? What were the things that quickly sold out in Chinese supermarkets?

Tan Tan: At the very beginning of the lockdown, in the last week of January, we experienced a similar kind of run on the shops. But Chinese people usually shop online, even to buy toilet paper. (Laughs) However, because of the combination of the lockdown and the New Year's holidays, for the first time there weren't enough companies at work to deliver goods, and even essential goods sold out frequently and were hard to come by. Especially fresh vegetables were scarce, and prices would sometimes go up like crazy. But as of March, the situation became much better, and the people from Wuhan could even get a lot of free food, donated by the other provinces.

The first thing I did after the lockdown ended? I took my dog out for a long walk along the lake. She is sixteen but she wagged her tail like a puppy. We both felt reborn!

Tan Tan, artist between Wuhan and Brussels

What was the hardest thing for you during the lockdown? In Dutch, there is this expression “huidhonger”, which literally translates to “hunger for skin”, meaning that you miss the simple kiss on the cheek or tap on the shoulder.

Tan Tan: You’re spot on! (Smiles) In China we don’t kiss people when we meet each other, but I do like the Belgian way. Simple kisses and hugs are very warming, and they gave me a lot of comfort while I was in Belgium. Another thing I miss a lot is travelling. I still can’t move everywhere in China smoothly, let alone leave the country. I cancelled three trips abroad during these past five months, including one heading back to Belgium. But the upside is that since the whole world is closed, we are allowing our earth to take a deep breath.

What was the first thing you did after the lockdown ended on 8 April?

Tan Tan: I went to see my grandmother, who stayed at home alone for about 70 days. And I took my dog out for a long walk along the lake. She hadn't been out for over a month. It was a perfect spring day, and she wagged her tail like a puppy – and she's already sixteen years old. We both felt reborn!

What was the atmosphere in the city like?

Tan Tan: It was quite relaxed. I saw people fishing, walking their dogs, playing cards along the lake, and already some people were on the way to or from their work. Nowadays, Wuhan is lifting more and more restrictions, and even the bars and live houses are reopening, but they are still not allowed to stage concerts or hold parties. I heard from a friend, who runs a bar, that they will probably be completely “set free” in June. But it is a fragile situation. Just last week, some new cases of asymptomatic infections were detected, so in some regions of Wuhan the situation is becoming tense again.

Is there something valuable that you picked up from this frightening experience? Something that you will continue to do after the crisis?

Tan Tan: Well, there is one thing: I followed an online course about the Bible’s Book of Revelation – before the real end of our world. (Laughs) I do believe in God (in a nonconventional way), although I don’t often go to church. I think many Christians would link this epidemic with scenes from the Book of Revelation. I personally don’t look at it as a realist prophecy. It is a “whistle” for all of us, a reminder that the world will be destroyed when we continue our soulless behaviour. But there will be or already exists another dimension of the world, which will open its doors to people who value their holy spirits. We should be aware of the whistling from our souls.

Tan Tan's dog

Let's end with redemption. You write that “it is time for us to go back to the sources of our world, then reshape the reciprocity between humans and animals and what humans are doing to the earth. This is more fundamental salvation than any vaccine.”

Tan Tan: How to reconnect with nature is a life-long question and task for me. After the lockdown, I feel strongly that I don't want to be “misplaced” anymore and live a life “jailed” in by the materialistic. I hope to find or create my own tribe, where people can live a more balanced life with regards to nature and spiritual sources. Wherever that may be.